"The Centralia Sentinel, of Lincoln’s home state, wanting nothing to do with fancy talk, had the speech begin, simply, 'Ninety years ago . . ."

– Adam Gopnik, searching for the most accurate account of the Gettysburg Address

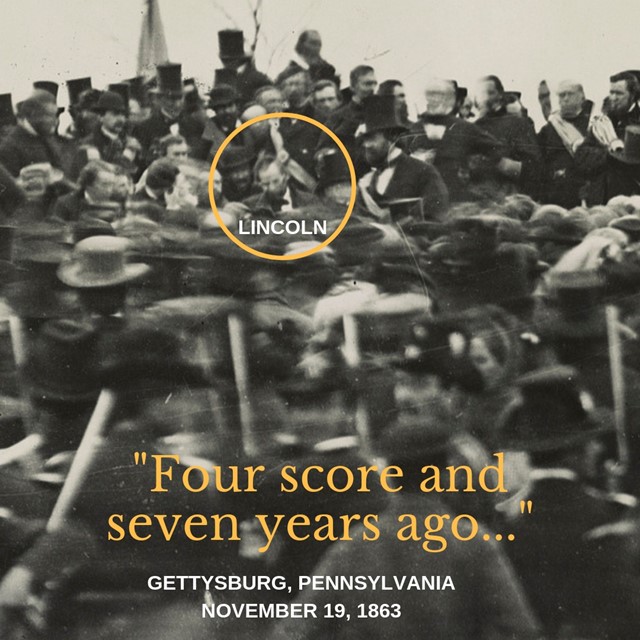

On November 18, President Abraham Lincoln made the train trip from Washington D.C. to Gettysburg, Pennsylvania. On the next day—Thursday, November 19, 1863—he would deliver a 270-word speech that is one of the most famous in American history.

The Historic Occasion

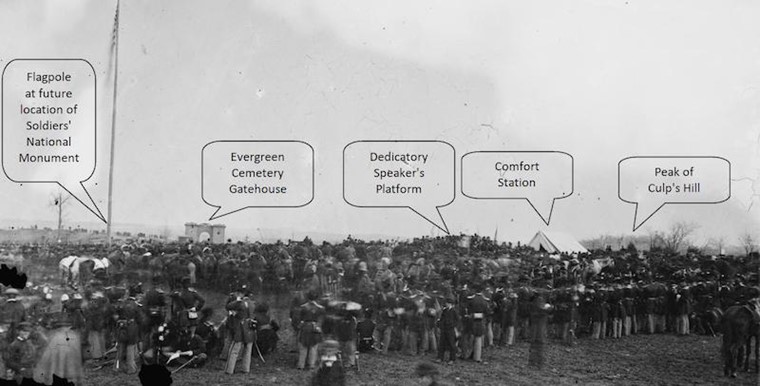

The occasion was the dedication of the Soldier’s National Cemetery, four and a half months after the Battle of Gettysburg.

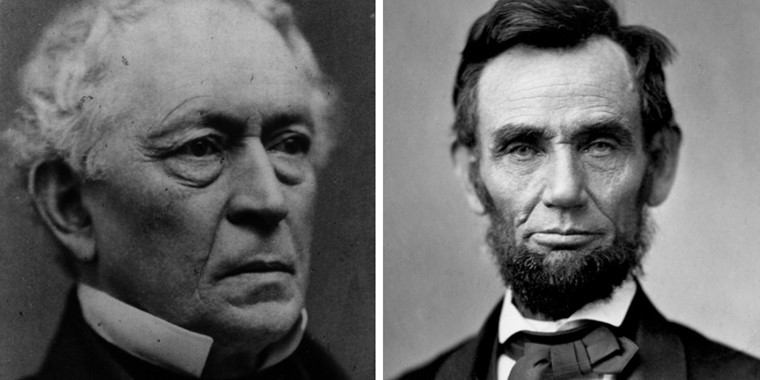

Lincoln followed orator and Harvard University president Edward Everett, who gave a two-hour speech full of long sentences and rhetorical flourishes in a style popular at the time. Not only did he have a long wait on a cold day, but Lincoln was obviously not well and would, a few days later, come down with a case of smallpox.

Edward Everett (left) and Lincoln (in a photograph made 11 days before his Gettysburg Address)

Edward Everett (left) and Lincoln (in a photograph made 11 days before his Gettysburg Address)

"I should be glad if I could flatter myself that I came as near to the central idea of the occasion, in two hours, as you did in two minutes."

– Edward Everett, who gave his 13,600 word Gettysburg Oration prior to Lincoln’s address

In 1931 at the age of 87, Sarah Cooke Myers recalled seeing the speech as a 19-year-old. She said, "I was close to the President and heard all of the Address, but it seemed short. Then there was an impressive silence like our Menallen Friends Meeting. There was no applause when he stopped speaking."

Newspapers at the time varied in their reports, depending on their political leanings. A New York Times account was complimentary and indicated several pauses for applause while the Chicago Times called it "silly, flat and dishwatery."

Photograph of the event on November 19, 1863.

Photograph of the event on November 19, 1863.

The 'Real' Gettysburg Address

There are many stories about how the speech came to be and at least five versions of the speech that exist. For most American school children, the Gettysburg Address is standard classroom fare, with experiences not unlike those of writer Roy Peter Clark:

As a schoolboy, I was told that the president had scribbled the speech on the back of an envelope during the train ride from Washington to Pennsylvania battle sites. That tale turns out not to be true, but I embraced it as a kid. If little George Washington could chop down a cherry tree and then own up to it, surely Honest Abe could push a pen on the back of an envelope.

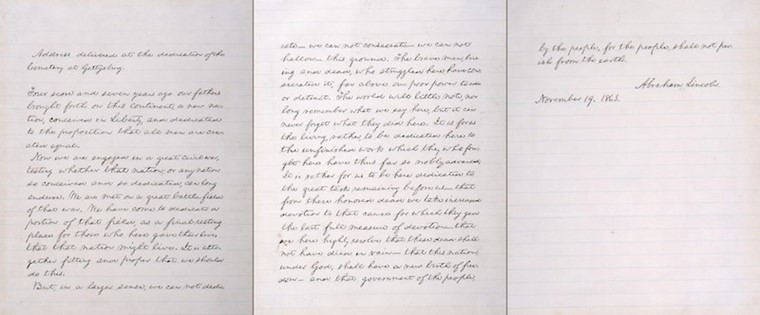

The John Hay version, referred to by many as the second draft of the Gettysburg Address.

The John Hay version, referred to by many as the second draft of the Gettysburg Address.

"Lincoln took the sentiment, stripped it of its orotundity, and produced one of the most stirring political statements in American history."

– New Yorker editor Dorothy Wickenden describing Lincoln’s writing style

A Distinctive Style

In writing about the accuracy of our recollections of Lincoln's words for The New Yorker, Adam Gopnik provides this perspective on Lincoln’s language:

Two prominent strains of rhetoric run through the period—the Biblical and the classical—and political ideas tend to get tinted by whichever of them the speaker uses.

Lincoln had mastered the sound of the King James Bible so completely that he could recast abstract issues of constitutional law in Biblical terms, making the proposition that Texas and New Hampshire should be forever bound by a single post office sound like something right out of Genesis.

What strikes a newcomer to Lincoln’s speeches, however, is how rare those famous cadences are; their simple, resonant language—“with malice towards none, with charity for all”; the concluding and opening lines of the Gettysburg Address—is memorable in part because there isn’t much of it.

The "Bliss" version, in Lincoln's handwriting, now used as the standard version of the Gettysburg Address

The "Bliss" version, in Lincoln's handwriting, now used as the standard version of the Gettysburg Address

A Model for Organizing a Message

At The Buckley School, we’ve used the Gettysburg Address to explore organization. In his book Sex, Power and Pericles, our founder writes of Lincoln’s knowledge of his audience, his powerful motivations, and his approach to achieving a larger goal:

Emaciated, eyes sunken and burning from their sockets as though from the back of his skull, he came to Gettysburg despairing for the resolve of his country. His purpose was not to commemorate a cemetery for the dead; it was to revive the spirit of the living.

And so, after invoking the words of Jefferson in the first paragraph of the Declaration, Lincoln proceeded as good essayists preparing a case do, deductively, ever narrowing the compass…moving from the great civil war to a great battlefield of that war, thence to a portion of that field—progressively reducing his target from the abstract to the concrete.

He concluded this first part of the body of his speech with the rhetorical summation: “It is altogether fitting and proper that we should do this.”

This signals to the attentive reader that a departure is imminent.

In the case of the Gettysburg Address, that departure is breathtaking; because Lincoln now moves inductively, from the concrete that we can grasp and bleed over to the abstract illumination to which the mind and spirit aspire.

Below, an excerpt about the Gettysburg Address from Ken Burns’s documentary The Civil War, including the story of how the photographer nearly missed capturing that image of Lincoln's address at all: