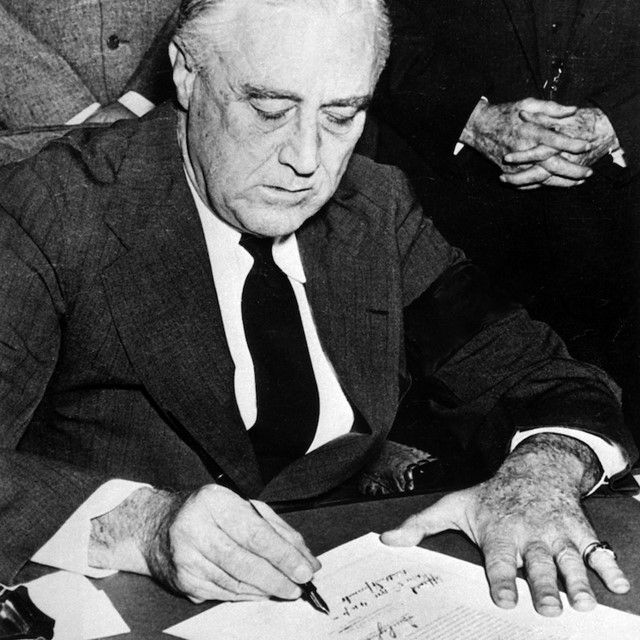

Above, Franklin D. Roosevelt signs the declaration of war against Japan shortly after delivering his famous speech.

"Yesterday, December 7, 1941, a date which will live in infamy, the United States of America was suddenly and deliberately attacked by naval and air forces of the Empire of Japan."

– President Roosevelt, opening his speech to Congress after the attack on Pearl Harbor.

It was lunchtime in Washington D.C. on December 7, 1941, when President Franklin Roosevelt got the call: Pearl Harbor had been attacked by the Japanese.

Less than 24 hours later, Roosevelt addressed a joint session of Congress, using the famous, and often misquoted, phrase: “a date which will live in infamy.”

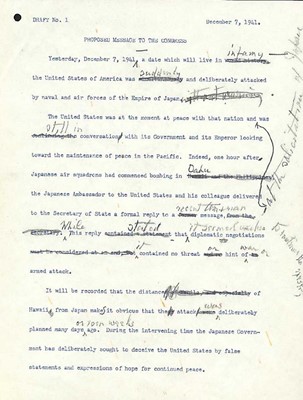

The first draft, with FDR's handwritten edits.

The first draft, with FDR's handwritten edits.

The U.S. National Archives provides a fascinating and thorough account of how the speech came to be written and revised, as well as images of the typed first draft with edits handwritten by Roosevelt.

Some of our favorite details from their story include:

- Before the revision, "a date which will live in infamy" was the less memorable, less emotional "a date which will live in world history."

- While he worked with speechwriters routinely, Roosevelt mostly wrote this speech himself, dictating it to his secretary, Grace Tully.

- Usually, the process for writing and revising his speeches took from three to ten days. This speech was created in under 24 hours, largely by FDR, on one of busiest, most tension-filled days of his presidency.

- His aide Harry Hopkins added one revision that led to the second most-quoted line of the speech. On the marked-up version, Hopkins wrote "Deity" and under that, notes which ultimately became: "With confidence in our armed forces— with the unbounding determination of our people— we will gain the inevitable triumph— so help us God."

- The length of the speech was about six minutes and was broadcast on radio nationwide with more than 80 percent of households tuning in.

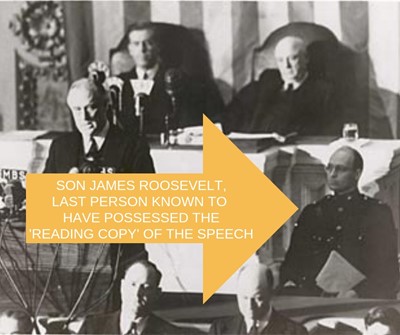

- The copy Roosevelt used for delivering the speech to Congress was misplaced and remains a missing document. "The 'reading copy,' typed triple-spaced and in a loose-leaf binder, has not been seen since James Roosevelt [FDR’s son] brought it back to the White House after the speech on December 8, 1941, and placed it atop a coat rack," notes the National Archives in a postscript to their original story.

President Roosevelt delivering his speech to Congress.

President Roosevelt delivering his speech to Congress.

More than 2,300 U.S. servicemen and 68 civilians were killed in the surprise attack on December 7. Within an hour of hearing the speech on December 8, Congress passed a declaration of war against Japan and the U.S. entered into World War II.

For more, find: