Even when we’re not aware of it, we’re using many of the same rhetorical techniques Aristotle, Cicero, Abraham Lincoln, Frederick Douglass, Winston Churchill, Martin Luther King, Jr. and other greats have employed in public speaking. Each month, our Buckley School resident students of classical rhetoric explain a rhetorical device that can improve your public speaking.

"Want to get a bunch of linguists on a problem lickety-frickin'-split? Just drop something naughty in the middle of a word or phrase. Like fan-freaking-tastic or too damn right or Judas H. Priest."

– James Harbeck writing about tmesis for "The Week"

BY JENNY MAXWELL AND JANA DALEY

Some classify it as a rhetorical device.

Wikipedia calls it a "linguistic phenomenon."

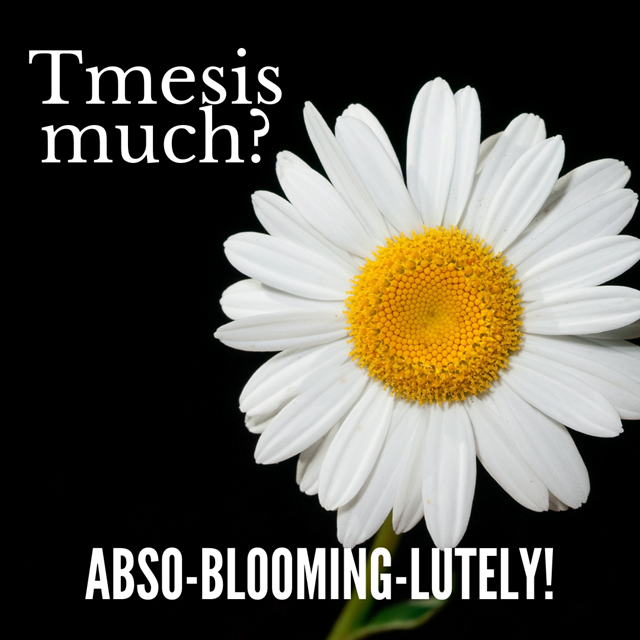

Tmesis—pronounced tuh-MEE-sis—comes from the Greek for "a cutting." It refers to the colorful practice of inserting one word into another word or phrase. A few examples:

- Eliza Dolitttle says "abso-blooming-lutely" in George Bernard Shaw’s play Pygmalion.

- "La-dee-freakin-da" became one of Chris Farley's signature phrases on Saturday Night Live.

- The Simpsons character Ned Flanders is known for his (mis)use of tmesis, inserting "diddly" into words such as "welcome" to come up with "wel-diddly-elcome."

How it works

As Ned Flanders demonstrates in The Simpsons, you can't shove the extra word in just anywhere.

James Harbeck wrote this about the art of tmesis in an article for The Week:

"When you insert a word for emphasis—be it fricking, bleeping, something ruder, or something less rude—you can't just stick it any old where. We know this because abso-freaking-lutely is fine but ab-freaking-solutely or absolute-freaking-ly is not.

"Whether it's in a word, a phrase, or a name—you stick the emphatic addition right before a stressed syllable, usually the syllable with the strongest stress, and most often the last stressed syllable.

"Look, these are rude, interrupting words. They're breaking in and wrecking the structure. That's the freaking point. But they still do it with a rhythmic feeling."

When you work with the rhythm of the words, Harbeck points out you can "add a whole nother word to just about any old thing."

Where to use tmesis

Obviously, tmesis is great for adding emphasis, color, or humor to your language. It shows up in spoken messages far more often than written ones.

Though we think of it as a natural part of modern slang, Shakespeare used the technique. H.L. Mencken wrote about it in 1936, according to Harbeck, who also says the rude f-word versions don't start showing up in print until the 20th century.

So we'll add our regular advice to 21st century speakers here: If you're going to cut in, be deliberate about your word choice. No need to carelessly offend your audience with the f-word when you can use with the "gosh darn" version and get the same effect.

Learn more

Australians call this rhetorical device "tumbarumba," a fan-freaking-tastic alternative to "tmesis." Here's the story on how that came about.

James B. McMillan uses the term "infixing" to talk about our American colloquial fondness for these expressions. He wrote an article about it for American Speech. You can find a link to the full article and an excerpt from it here.

Find James Harbeck’s article "Why linguists freak out about 'abso-freaking-lutely’" for The Week here.