Even when we’re not aware of it, we’re using many of the same rhetorical techniques Aristotle, Cicero, Abraham Lincoln, Frederick Douglass, Winston Churchill, Martin Luther King, Jr. and other greats have employed in public speaking. Each month, The Buckley School's resident students of classical rhetoric explain a rhetorical device and show us how it’s being used for good and for evil.

BY JANA DALEY and JENNY MAXWELL

“He don’t love you like I love you.”

– Tony Orlando and Dawn making it to the top of the Billboard chart in 1975 using enallage

To the dismay of grammarians far and wide, some of our most memorable phrases are the ones that break the rules.

Turns out that defying the rules of standard usage is a rhetorical device, one you’ll find at work in rap, country music, advertising headlines, and political speeches.

There’s a word for it. Enallage. Pronounced much like analogy. eh-NAHL-uh-jee. And you’re likely to see examples of it everywhere you look. Right now. Today.

Mick Jagger, most likely engaging in enallage in the Netherlands in 1976. (Netherlands National Archives)

Mick Jagger, most likely engaging in enallage in the Netherlands in 1976. (Netherlands National Archives)

Mom can’t get no satisfaction

It's hard to imagine Mick Jagger singing “I can’t get any satisfaction,” despite your mother’s insistence that his double negative says he’s getting satisfaction aplenty (which was probably true all the way around).

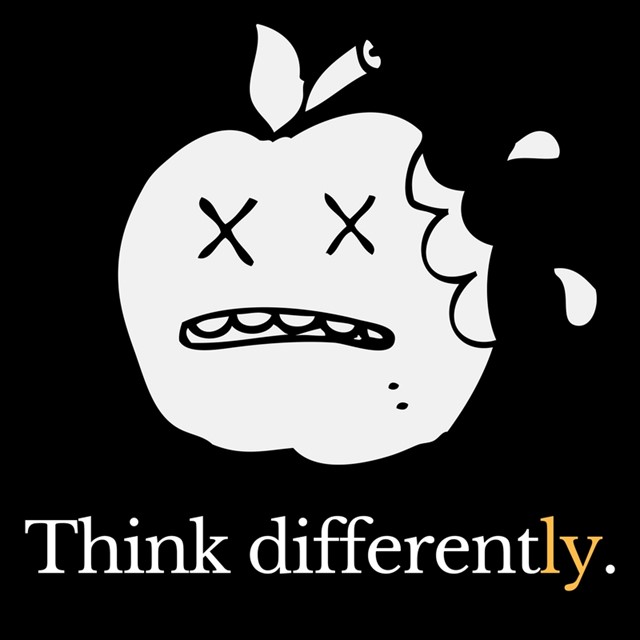

Or how about the Apple advertising slogan “Think Different,” which sent many grammarians into a tizzy? Here’s the Wikipedia write up on that:

The grammaticality of "Think Different" is disputed. Some say it is not correct in standard English: being a verb, "think" needs to be modified by an adverb, which would be "differently." On the other hand, standard English has many flat adverbs such as "hard" which lack the characteristic -ly ending of most adverbs (and think hardly means almost the opposite of think hard). There are also non-standard varieties of English in which "different" would be the normal, adverbial form.

According to [Steve] Jobs's official biography, "Jobs insisted that he wanted 'different' to be used as a noun, as in 'think victory' or 'think beauty.'" Jobs also specifically said that "think differently" wouldn't have the same meaning to him. Also, Jobs wanted to make it sound colloquial, like the phrase "think big."

Steve Jobs recognized—as other influencers have—that buttoned-up speech isn’t always as influential as the alternatives.

Curiouser and more curious indeed

Examples aren’t limited to modern language use. In Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland, Alice says “curiouser and curiouser.”

A copy editor might point out that Alice should have said “more and more curious.” A novelist might point out that this is a character speaking, not a grammarian.

But we can all agree that “curiouser and curiouser” is now an expression we love to say and hear, something “more and more curious” could never be.

Solecism vs. Enallage

Does this mean that students in the halls of learning can now cite enallage to excuse their mistakes?

No. There’s another word for the errors of usage that are unintentional—solecism. That term originates from a Greek word inspired by Soli, the name of a colony in Turkey settled by ancient Greeks. Soli residents were widely known for their struggles to speak proper Greek.

Enallage also has Greek origins and means “interchange.” Thus, enallage refers to breaking the rules in a deliberate way, solecism describes rule-breaking because you don’t know any better than the poor disparaged folk of Soli.

For a look at how the Think Different campaign came about, including the dropping of the “ly,” here’s an interesting read.

And below, Tony Orlando and Dawn making the use of enallage sing: