"Character is the primary element that a speaker brings to the stage. Everything else can be learned," writes Reid Buckley. In his book "Strictly Speaking," he looks at the virtues and vices a speaker can project. We’re providing excerpts here in our online magazine.

"The forensic demands of lying well, or credibly, are identical to the forensic demands on the speaker who is in fact truthful."

– Reid Buckley

Introduction: Virtues and Vices

Craft is demanded of the performer—how to make the most of one's voice, one's face, one's hands, one's body—which, when perfected, can be lifted to the level of art. But these are useless artifices unless the speaker projects certain virtues, suppresses certain vices.

I've selected the good and the bad that, in my forty-five years as a performer and fifteen years as a teacher, strike me as paramount. Keep this in mind: You must extrapolate.

Because there's a distinction to be drawn between the social personality and the stage personality. They do differ; they can even be antipodal.

Our concern is what one projects from the stage, not what one happens to be. Of the vices and virtues discussed, you may be afflicted by none personally, graced by none; but their projection may either undermine or fortify your performance. We’re talking about virtual reality.

The Virtues: Honesty

That is to be more precise and…honest…the appearance of which.

There are circumstances when it becomes the obligation of the speaker to stretch or embroider the truth, tell not quite the whole truth, equivocate, lie.

This isn't a book about ethics; it's about how to speak in public well and effectively. There are occasions, alas, when one's duty may be to lie oneself blue in the face, yet one must project from the platform an air of total candor.

Traits

The impression of honesty is projected when the speaker qualifies what he is saying—the policy or cause he is upholding—in the narrowest terms and with an evident desire not to claim too much for what he favors:

- By citing the arguments against the cause or policy he deems best and doing them full justice

- By being quick to cede minor points in which his is proved mistaken (or has been found eliding)

- By graciously thanking whoever (may he fry in Hell) brought the errors to his attention and apologizing for having given the wrong impression

- By being a trifle diffident in praising his side of the argument, using such phrases as "I don't want to claim too much for what I'm suggesting…"

From the Stage

The speaker's demeanor should at all time be composed, his expression kind and judicious. When listening to an objection, he should do so with evident total concentration, frowning, head bent or cocked toward the interrogator—nodding as though half in agreement or freshly reconsidering his position.

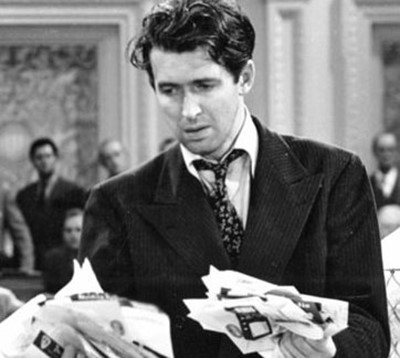

He should hesitate before delivering his answer, never flinging a hasty, sharp, or dismissive retort. Oh, he must be wily, projecting himself as a Jimmy Stewart facing down Lionel Barrymore.

The Spanish call it cara (face). We call it brass. I could draw up a list of master rogues in the public arena who have succeeded brilliantly in never telling the truth in such honest mien that they chalk up stunning approval ratings in poll after poll, lie after lie, year after year.

Now don't be foolish. The forensic demands of lying well, or credibly, are identical to the forensic demands on the speaker who is in fact truthful:

- Be fair-minded

- Don't overstate your case

- Admit errors gladly and graciously

- Listen hard to objections

- Weigh alternative proposals well before rejecting them

- Avoid hast or irascible reactions

- Never flinch from a tough question

Jimmy Stewart in "Mr. Smith Goes to Washington"

Jimmy Stewart in "Mr. Smith Goes to Washington"

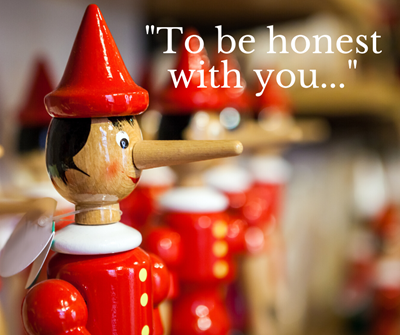

Do not make this common mistake: Using the phrase "To be honest with you…" Hmmm. Were you not previously being honest with us? Two minutes from now, will you cease to be honest with us? The speaker who calls attention to his virtue places it in doubt.