"Tell me a fact and I'll learn. Tell me the truth and I'll believe. But tell me a story and it will live in my heart forever."

– Proverb

BY JENNY MAXWELL

You’ve probably read it in a business publication somewhere (or maybe you watched the final episode of Game of Thrones): "Whoever tells the best story wins."

The corporate world has embraced storytelling as a persuasive tool so of course, there have to be winners.

But I was recently reminded of how a story can teach. I was working with a group of Defy Ventures participants. You may know that Defy is a program that helps people in prison develop their skills to plan a business and launch it.

Arriving at Defy's L.A. office to lead a workshop.

Arriving at Defy's L.A. office to lead a workshop.

One man in our group had been released just two weeks prior. As a teen, he’d been a gang member in L.A. He’d been incarcerated since he was 16. He’s 40 now, and he wants to speak to teens in high schools and in juvenile detention programs. He wants them to see the value of making better decisions, even if a bad decision in the past has caused them to be where they are now.

'This is not Scared Straight'

As soon as he starts speaking, it's clear he has the right idea. He understands his audience and he makes that clear with his opening line: "This is not scared straight," he says. His classmates applaud.

One good decision he'd made that he wants to tell teens about was his choice to learn to speak confidently. As we work on his message, we realize concepts like "show initiative" and "learn to advocate for yourself" may be hard for his audience to comprehend. Even I'm not sure what that means for someone in prison.

So he tells me his story of learning to speak up in prison support groups, then getting the courage to raise his hand and speak in a class. And how that helped him learn to stand up and speak in front of small groups. And why that was important, because it enabled him to speak before the parole review board, make a case for himself, and finally have the freedom to swim in the ocean again after 24 years.

Yes, you can say his story makes a pitch and builds a personal connection to his audience, two of the highly-touted reasons for using stories in business presentations.

But in telling the story, he will teach his young audience (as he showed me) how to make better choices and show them exactly what those choices can look like. His story can serve as their step-by-step instruction manual for turning life around when you fear you have nowhere good to go.

To tell stories that teach, we might want to think about how our favorite teachers and professors have used them to teach us.

To tell stories that teach, we might want to think about how our favorite teachers and professors have used them to teach us.

Storytelling to teach in business settings

With that experience in mind, I did a little research on stories that teach and found insights from psychology professor Melanie Green. A few years ago, she took a look at storytelling in teaching for the Association for Psychological Sciences.

While her conclusions felt like common sense to me and lined up with my own experiences as a student, she also used research to back them up:

- Storytelling improves recall because narrative gives a framework for remembering facts.

- Stories are a natural way for processing information. We’ve all been hearing stories since birth.

- The imagery in stories helps students "see" abstract concepts.

- Stories are often more interesting and less intimidating than raw data, so even telling the story of how that data was collected can be a powerful tool for researchers and teachers.

She also presents some suggestions for telling those stories in classrooms that line up with how we teach storytelling for business presentations.

Only tell a story that makes a clear, relevant point

I often say that the stories you tell in a business presentation can’t be like the stories my mother tells (though I do love her dearly): Your business stories have to be short and make a point.

Green agrees, urging professors to:

Keep the story clean and to the point. Furthermore, if a story doesn’t quite match the concept you are trying to demonstrate, you may be better off omitting it.

Important to remember any time you use a story: the audience may not automatically get the point you hope to make.

Important to remember any time you use a story: the audience may not automatically get the point you hope to make.

Fill in the blank "I’m telling you this story because ____________"

I learned this from a colleague who used to coach stand up comics. She says every time you tell a story as a professional, you need to be able to fill in that blank for yourself. You may also need to explicitly fill it in for your audience.

Here’s how Green writes about it for teaching:

Because listeners have their own interpretations of the point of stories, it is your responsibility as an instructor to make the message of the story clear, and draw links between the story and the abstract principles it demonstrates. Beginning students, especially, may not be able to make these connections on their own.

Give context so we know how the story relates to the data

Despite the popularity of storytelling in the business world, I still encounter a lot of skepticism. I even talk about there being a story-averse audience—those in the sciences and other data-driven fields who think you are using a story to manipulate the all-important facts.

So give context for your story. Is it typical? Unlikely? How does it stand up alongside the facts?

For knowledgeable and skeptical audiences, your ability to provide that context is critical. Without it, you may lose credibility in their eyes.

When teaching, the context is important too. Here’s what Green writes:

Your use of stories should be integrated with reference to empirical evidence, so that students do not come away with the impression that a single story, even an especially vivid and compelling one, should be understood as proof for a particular position.

Make sure your stories don't misrepresent the data--or undermine your credibility--by providing context.

Make sure your stories don't misrepresent the data--or undermine your credibility--by providing context.

Don’t, however, let the facts limit your menu of story options

While you don’t want a story to mislead your audience, a powerful story does not have to be a true one.

Think of how a fairy tale might work as an analogy—a short-cut to understanding. Or how a scene from a movie, re-told by you, could frame the issue in a more accessible way.

Here’s what Green wrote about that for professors trying to connect with college students:

Research results need to be true, but stories do not. Do not be afraid to use stories from fiction, especially well-known fiction. For instance, the children’s story “The Emperor’s New Clothes” demonstrates social influence principles; the interactions between Iago, Othello, and Desdemona in Shakespeare’s play Othello provide a powerful illustration of the importance of perceptions over objective reality.

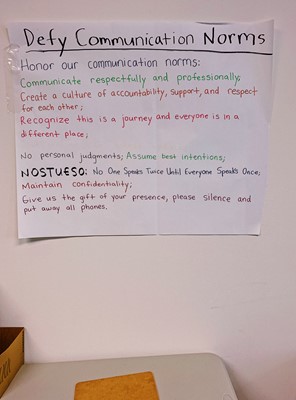

Defy members generated their own guidelines for communicating, posted on our classroom wall.

Defy members generated their own guidelines for communicating, posted on our classroom wall.

Learn more:

To find the complete article from Dr. Melanie Green, go here.

To learn more about Defy Ventures and the powerful stories of their emerging entrepreneurs, visit their website.

For more on the power of storytelling, you might also like one of our favorite books.