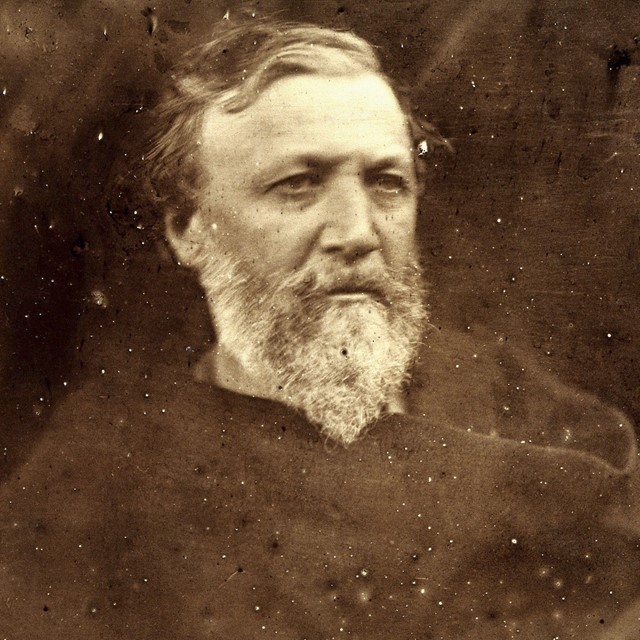

The Buckley School's founder believed that all public speakers should hone their presentation skills by reading poetry out loud. We keep that worthwhile practice alive by including a poem in our magazine each month for you to read aloud. Above, Robert Browning photographed by Julia Margaret Cameron (Wellcome Library, London) in 1865 when Browning was 57.

"Of course you are self-conscious—How could you be a poet otherwise? Tell me."

– Elizabeth Barrett in a letter to Robert Browning

Robert Browning's reputation had its ups and downs, even during his lifetime but he endures as the poet who gave the world some of its favorite stories and characters, as well as one very satisfying real life love story.

Born to parents who could afford to have a poet in the family, Browning decided on his career path as a child and never wavered. He completed his first book of poems at age 12. As a young adult, he became well-known for his story of the Pied Piper in verse and for his book, Dramatic Lyrics. Among those who admired it was poet Elizabeth Barrett.

Often considered poetry's favorite power couple, Elizabeth Barrett Browning and Robert Browning. (Portraits by Thomas B. Read)

Often considered poetry's favorite power couple, Elizabeth Barrett Browning and Robert Browning. (Portraits by Thomas B. Read)

Browning and Barrett began a correspondence that led to a romance. When Barrett's father would not permit his daughter to marry and leave home, Browning (aged 34 and still living with his parents) married her in secret and the couple eloped to Italy in 1846. They lived in Florence for the rest of Barrett's life and had one son, Pen.

Browning took progressive positions on many issues of the day, including women's equality, abolition of slavery, and animal rights. He continued to write poetry, apparently unhindered by popular opinions about his work. By the time he died in 1889, he was well-established as a leading poet and philosopher.

Not long before his death, he also created one of the oldest surviving recordings made by a person of note. At a dinner party on April 7, 1889, one of Edison's British representatives made a wax cylinder recording of Browning reading his poem "How They Brought the Good News from Ghent to Aix".

Here's a portrait by Allesandro Allori of the teenaged duchess who inspired Browning's poem. (North Carolina Museum of Art)

Here's a portrait by Allesandro Allori of the teenaged duchess who inspired Browning's poem. (North Carolina Museum of Art)

Browning is strongly associated with poems in the form of dramatic monologues. One of his best-known is "My Last Duchess", first published in that volume that attracted Elizabeth Barrett's admiration.

"My Last Duchess" is thought to be based on the true story of Lucrezia di Cosimo de 'Medici, who at 14 was married to the 25-year-old Duke of Ferrara. He abandoned her when she was 15, and she died at age 17. Rumors said the cause of her death was poisoning, though historians now believe it's likely she died of tuberculosis.

"My Last Duchess" hints at the story, in the voice of the cruel duke, making it a perfect read aloud poem for working on your timing and dramatization skills—even if there's nothing you can do to help the poor duchess.

My Last Duchess

That's my last Duchess painted on the wall,

Looking as if she were alive. I call

That piece a wonder, now; Fra Pandolf's hands

Worked busily a day, and there she stands.

Will't please you sit and look at her? I said

"Fra Pandolf" by design, for never read

Strangers like you that pictured countenance,

The depth and passion of its earnest glance,

But to myself they turned (since none puts by

The curtain I have drawn for you, but I)

And seemed as they would ask me, if they durst,

How such a glance came there; so, not the first

Are you to turn and ask thus. Sir, 'twas not

Her husband's presence only, called that spot

Of joy into the Duchess' cheek; perhaps

Fra Pandolf chanced to say, "Her mantle laps

Over my lady's wrist too much," or "Paint

Must never hope to reproduce the faint

Half-flush that dies along her throat." Such stuff

Was courtesy, she thought, and cause enough

For calling up that spot of joy. She had

A heart—how shall I say?— too soon made glad,

Too easily impressed; she liked whate'er

She looked on, and her looks went everywhere.

Sir, 'twas all one! My favour at her breast,

The dropping of the daylight in the West,

The bough of cherries some officious fool

Broke in the orchard for her, the white mule

She rode with round the terrace—all and each

Would draw from her alike the approving speech,

Or blush, at least. She thanked men—good! but thanked

Somehow—I know not how—as if she ranked

My gift of a nine-hundred-years-old name

With anybody's gift. Who'd stoop to blame

This sort of trifling? Even had you skill

In speech—which I have not—to make your will

Quite clear to such an one, and say, "Just this

Or that in you disgusts me; here you miss,

Or there exceed the mark"—and if she let

Herself be lessoned so, nor plainly set

Her wits to yours, forsooth, and made excuse—

E'en then would be some stooping; and I choose

Never to stoop. Oh, sir, she smiled, no doubt,

Whene'er I passed her; but who passed without

Much the same smile? This grew; I gave commands;

Then all smiles stopped together. There she stands

As if alive. Will't please you rise? We'll meet

The company below, then. I repeat,

The Count your master's known munificence

Is ample warrant that no just pretense

Of mine for dowry will be disallowed;

Though his fair daughter's self, as I avowed

At starting, is my object. Nay, we'll go

Together down, sir. Notice Neptune, though,

Taming a sea-horse, thought a rarity,

Which Claus of Innsbruck cast in bronze for me!