Even when we’re not aware of it, we’re using many of the same rhetorical techniques Aristotle, Cicero, Abraham Lincoln, Frederick Douglass, Winston Churchill, Martin Luther King, Jr. and other greats have employed in public speaking. Each month, The Buckley School's resident students of classical rhetoric explain a rhetorical device and show us how it’s being used for good and for evil.

BY JENNY MAXWELL and JANA DALEY

"Time flies like an arrow. Fruit flies like a banana."

– Groucho Marx

No, paranomasia is not a fear of the paranormal. That would be called common sense.

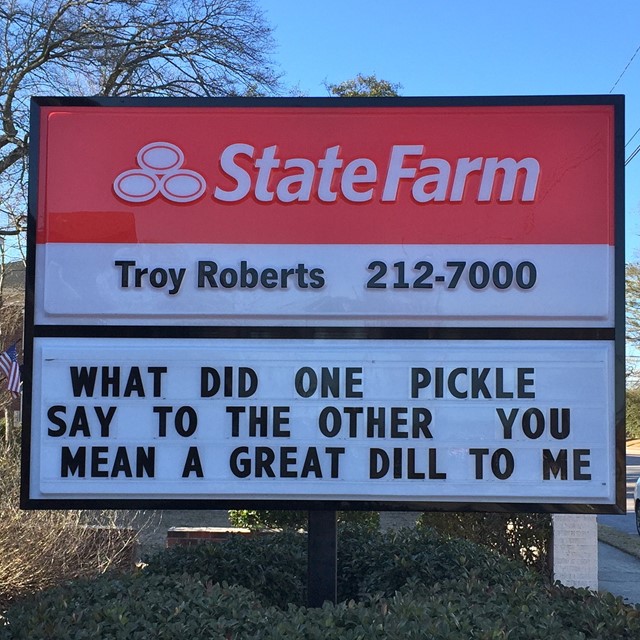

Paranomasia is simply the wordplay we average folk call a pun—a form of humor both loved and loathed (sometime simultaneously within the same brain at the same moment), a rhetorical device that has a long history in both writing and speech. The early master of the comedic play, Roman playwright Plautus, was a paranomasia practitioner.

Paranomasia can fall into a variety of categories (as described on Wikipedia):

- Homophonic—words that sound alike. Example: George Carlin's "atheism is a non-prophet institution"

- Homographic—words that are spelled alike (making this better suited for writing than speech). Example: Douglas Adams's "You can tune a guitar, but you can't tuna fish. Unless of course, you play bass."

- Compounded—a collection of several puns that build on each other in a sentence or series of sentences. Example: (see above)

- Recursive—wordplay in which the second aspect requires understanding of the first. Example: "a Freudian slip is when you say one thing but mean your mother.”

In spoken communication, paranomasia can add humor, make a speaker seem witty, or make a line memorable.

Some say paranomasia can be used to improve understanding and recall in classroom settings.

And while punning may come easily for some and help information pass easily to others, it may not be the best bet. Giving advice to junior copywriters at advertising agencies, one blogger writes:

A pun is usually followed by a groan from the people hearing it or reading it. It's rarely followed by raucous laughter, and it's almost never thought of as clever or sophisticated. It is what it is; a play on words that relies on phonetics.