"I couldn’t believe how this was. I put on my uniform, and I went out on the field to warm up, but nobody wanted to warm up with me. I had never been so alone in my life. I stood there alone in front of the dugout for five minutes. Then Joe Gordon, the second baseman who would become my friend, came up to me and asked, ‘Hey, rookie, you gonna just stand there or do you want to throw a little?’ "I will never forget that man.”

– Larry Doby, recalling his first game with the Cleveland Indians

A National Baseball Hall of Fame inductee, Larry Doby was also a native of Camden. A statue of him stands just a couple of blocks up Broad Street from The Buckley School.

Like Jackie Robinson, Doby was more than an incredible athlete: He was a civil rights leader, breaking barriers as the first African-American to play in the American League and the first African-American to hit a home run in a World Series Game. He was one of the first African-American all-star team members and the major league's second African-American manager.

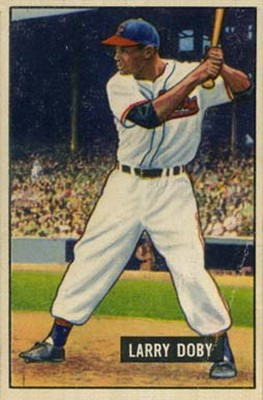

Larry Doby, Cleveland Indians Centerfielder, baseball card from 1951

Larry Doby, Cleveland Indians Centerfielder, baseball card from 1951

And like Robinson, he endured a great deal. Sports Illustrated wrote that Doby had to suffer the same indignities without the support and media attention. Or as Doby himself told Jet magazine, "Jackie got all the publicity for putting up with it (racial slurs). But it was the same thing I had to deal with. He was first, but the crap I took was just as bad. Nobody said, 'We're gonna be nice to the second Black.'"

A Childhood Spent in Camden

Larry Doby was born in Camden on December 13, 1923.

Life in Camden wasn’t easy for him. His father, a horse groomer and semi-pro baseball player, drowned when Doby was young. Schools were segregated in South Carolina, and Doby attended Jackson School, which was on Campbell Street southwest of The Buckley School.

But Camden was also where Doby learned to play baseball.

Doby described his childhood to a reporter for the Charleston Post and Courier: "Growing up in Camden, we didn't have baseball bats. We'd use a tree here, a tin can there, for bases."

Breaking Barriers in More than One Sport

At age 14, Doby moved to Paterson, New Jersey, to live with his mother’s family.

He became known there for his athletic abilities in baseball, basketball, football, and track.

Not only did Doby play baseball at the top of the sport, he was also the first African-American to play professional basketball in the American Basketball League.

Getting the Recognition He Deserves

You’ll find the statue of Doby on the front lawn of the Camden Archives and Museum at Broad and Dekalb streets. It’s the work of local artist Maria Kirby-Smith and has its own barrier-breaking story. You can read more about that in this column about the statue’s dedication by Kathleen Parker for The Washington Post.

“You know, it’s a very tough thing to look back about things that were probably negative. (On a day like this one) you put those things on the back burner. You are proud and happy that you’ve been a part of integrating baseball to show people that we can live together, we can work together and we can be successful together.”

– Larry Doby, in his Hall of Fame induction speech

Meanwhile, a group of U.S. Senators and Representatives have introduced a bill to honor Doby with a Congressional Gold Medal, to mark the 70th anniversary of Doby’s debut with the American League. Doby made his debut with the Cleveland Indians on July 5, 1947.

More about Larry Doby:

- Here's an interview with his son and the unveiling of a statue of Doby in Cleveland.

- You can see Doby speaking at his Hall of Fame induction here.

- Here’s a recent story from Sporting News and this column, from a fan who saw Doby play his first games in Cleveland.

- For more on what Jackie Robinson, Larry Doby and other African-American major league players faced, see this article from The Atlantic.