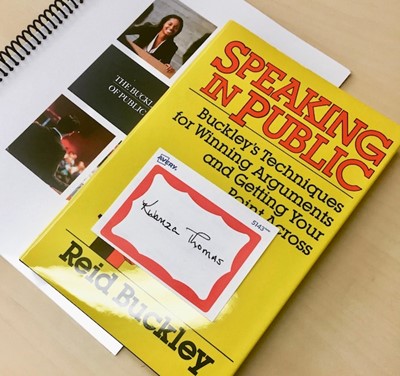

Thirty years ago, The Buckley School launched its flagship program and our founder Reid Buckley published his first book on public speaking. To mark the anniversary this year, we’ll be featuring instructional excerpts from that book—"Speaking in Public: Buckley’s Techniques for Winning Arguments and Getting Your Point Across"—sometimes augmented with a few of our notes on his words.

From Chapter 1: Making a Fool of Yourself

What if one’s quotidian fare is dull, dry stuff, like maybe actuarial tables, or virus cell counts, or military regulations regarding the approved correct digging of field latrines? How does one sweep people off their feet with that kind of raw material?

Stop feeling sorry for yourself. There is no topic under the sun that cannot be made interesting. Some topics just demand more effort on the speaker’s part.

The interest quotient of any speech is in direct ration to the interest and energy put into the topic by the speaker.

Engaging their imagination by using yours

Even corporate balance sheets can be made of gripping moment. If one is reporting on the sickly rate of a company’s return on investment, one need not just set it forth. One can compare it with the historical rate or the company, with the rate of return in the industry, and with—for example—a much more favorable rate posted by a competitor.

This may require some research, but the sweat one puts into any report or paper tends to be reflected in the energy level with which one delivers that report or paper, and it is the energy in the speaker’s voice—the note of keen interest on his part—that ignites interest in the audience.

To celebrate The Buckley School's 30th anniversary, we've been giving everyone who attends our Executive Seminar their own copy of this book.

To celebrate The Buckley School's 30th anniversary, we've been giving everyone who attends our Executive Seminar their own copy of this book.

Making the numbers relevant

When a speaker is imaginative in his presentation, the audience will sit up and pay attention. One does not simply reel off the figures: One assigns a priority of significance to them, shaping the presentation in an intelligent manner.

“Sales are at record levels, production is up, the backlog of orders is satisfactory, but the area in this past quarter’s performance that bears watching is this: the return on investment. It isn’t good. It hasn’t been good for the past five quarters.”

Moving from abstract to concrete

What one is trying to accomplish is to bring down to whomever one is addressing what the dry figures, when interpreted, signify personally to them. That is always the speaker’s object: bringing his thesis home to the audience, making the abstract concrete and therefore real.

It is in fact easy enough to capture and hold the attention of soldiers when one instructs them in how and where to dig field latrines, because it is evident to the dumbest recruit that the consequences are far from dry. Nor are they abstract.